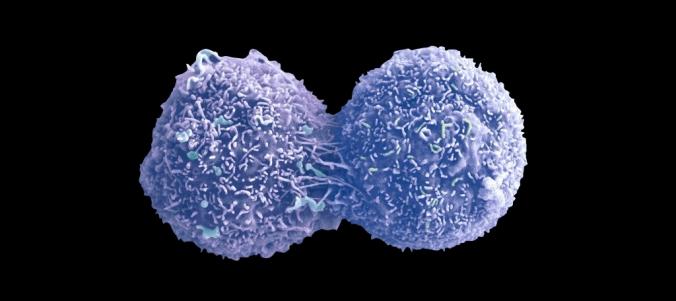

A big part of what biologists do is to catalog the diversity of life. That diversity can take many forms. There are hundreds of thousands of species of beetles on Earth, for example. There are also some untold number of genes in the human genome that play a part in cancers of different types.

In his early years, the Nobel-Prize winning biologist James Watson infamously derided nature’s catalogers as “stamp collectors.” Simply creating lists didn’t seem to get at the heart of things–like the structure of DNA, which Watson helped decipher. But it’s impossible to fully understand nature only by taking it apart into its smallest parts. An organism is a sum of those parts, as is an ecosystem or a biosphere. Watson implicitly acknowledged that fact when he became the first director of the Human Genome Project, which sought to sequence all our genes. The catalog itself–whether it’s a catalog of plant species in a forest, or bacteria in a microbiome, or genes in a genome–doesn’t automatically reveal insights on its own. But scientists can explore a catalog to test their ideas about large-scale biology. Continue reading “How Do You Know When You’ve Found Them All? A Question That Applies To Beetles and Cancer Genes Alike”