The New York Times, June 11, 2014

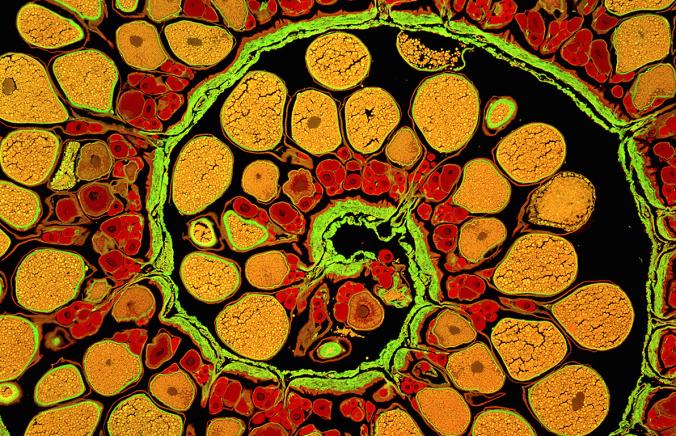

Half a billion years ago, a new study suggests, your ancestors may have looked like this:

This two-inch, 505-million-year-old creature belonged to the lineage that would later produce sharks, eels and other fish — along with birds, reptiles and mammals like us. This early vertebrate, known as Metaspriggina, was something of a mystery for years, known only from a pair of ambiguous fossils. But recently, scientists unearthed a trove of much more complete Metaspriggina fossils.

As they report today in the journal Nature, the new fossils offer a remarkably detailed understanding of the first vertebrates, helping scientists understand how major parts of our own anatomy — from eyes to jaws to our muscles — evolved.

Continue reading “A Long-Ago Ancestor: A Little Fish, With Jaws to Come”