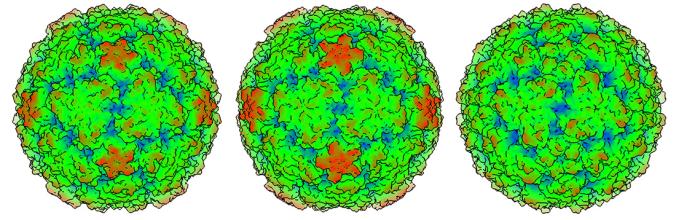

Like me, you may be snuffling with a cold today. You’re infected–typically in your nose–with a virus. The dominant cold-causing virusers are known as rhinoviruses, and they’re quite lovely. Here’s I’ve embedded a video of one, which lets you orbit the virus like you’re visiting an alien moon:

(The video is based on this 2014 study of the structure of the rhinovirus shell.)