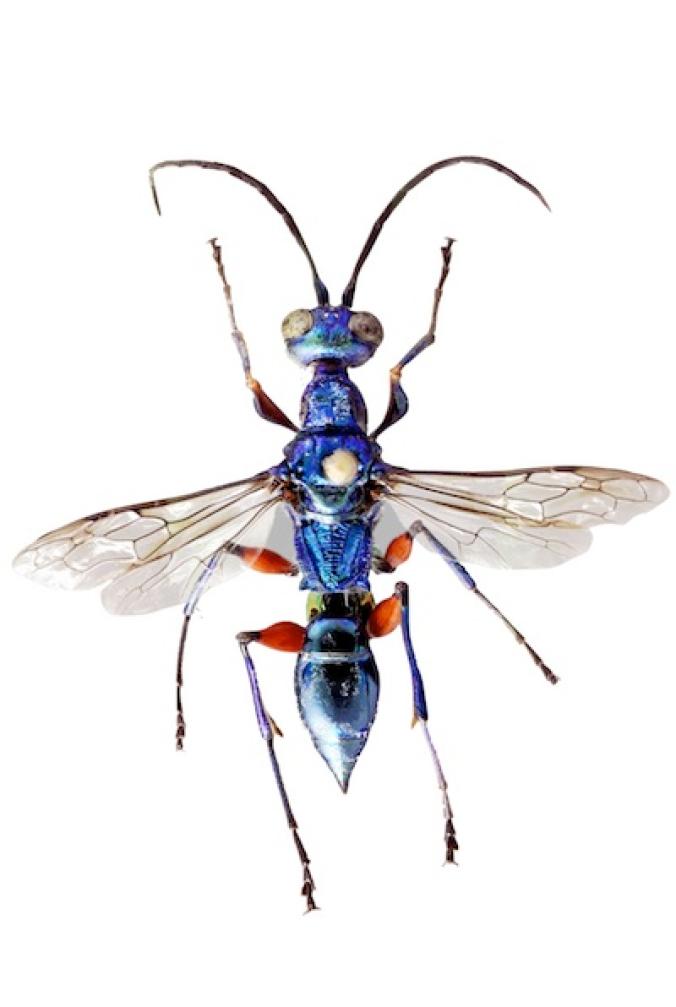

Parasites can take many forms. Just this week, I’ve written about a giant virusthat reproduces inside amoebae (and has survived being frozen 30,000 years in permafrost), along with a wasp that performs brain surgery to zombify hosts for its young. Viruses and wasps are radically different organisms–some would say that viruses don’t even deserve the label of organism. And they make use of their hosts in different ways. The virus sits inside a cell, manipulates its biochemistry to build virus proteins and DNA. The wasp, on the other hand, sips fluids inside a still-living roach, and builds its own proteins and DNA–and then becomes a free-living creature that can climb out of its host and fly away.

So why are they both parasites? The answer lies beyond the details of anatomy and molecules. It’s all about relationships. Continue reading “The Information Parasites”