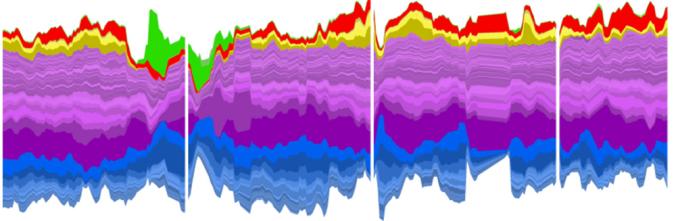

If you explore our genealogy back beyond about 370 million years ago, it gets fishy. Our ancestors back then were aquatic vertebrates that breathed through gills and swam with fins. Over the next twenty million years or so, our fishy ancestors were transformed into land-walking animals known as tetrapods (Latin for “four feet”).

The hardest evidence–both literally and figuratively–that we have for this transition comes from the fossil record. Over the past century, paleontologists have slowly but steadily unearthed species belong to our lineage, splitting off early in the evolution of the tetrapod body. As a result, we can see the skeletons of fish with some–but not all–of the traits that let tetrapods move around on land. (I wrote about the history of this search in my book At the Water’s Edge; for more information, I’d suggest Your Inner Fish, by Neil Shubin, who discovered Tiktaalik, one of the most important fossils on the tetrapod lineage.)