We know they evolved from dinosaurs about 150 million years ago, but it remains to be discovered precisely how the DNA of ground-running dinosaurs changed–a transformation that turned arms into wings, produced aerodynamic feathers, and created a beak. It’s possible that some clues to those genetic changes can be found in living birds themselves. By blocking some of the recently evolved steps in the development of bird embryos, we might be able to get birds to grow some dinosaur anatomy.

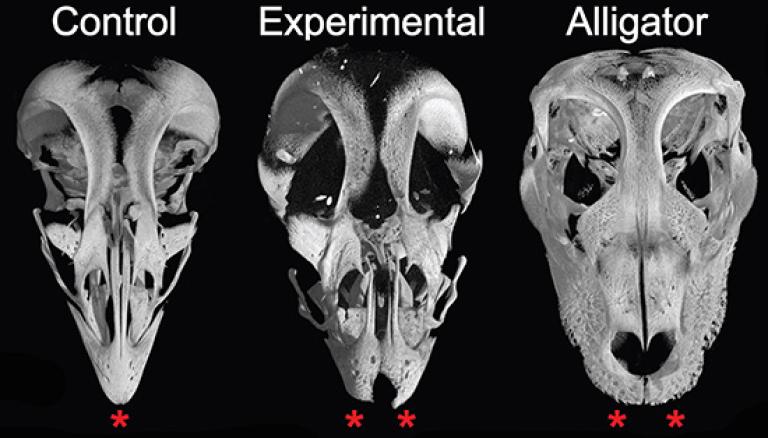

A team of researchers recently used this approach to understand how dinosaur snouts turned into bird beaks. Beaks are really just insanely extravagant versions of little bones called premaxillae. (You’ve got a pair just behind your front teeth.) The researchers blocked some proteins produced on the face of chicken embryos and found that the chickens failed to make beaks. Instead, their premaxillae became an unfused pair of bones–a lot like you might find in living beakless relatives of birds, such as alligators. Here, a normal chicken skull is on the left, an altered one is in the middle, and an alligator is on the right.

As I write in my column today in the New York Timesin the New York Times, some researchers remain skeptical that these chickens are really developing the beakless heads of their ancestors–that they’ve run evolution in reverse, in effect. More precise experiments on chicken DNA could confirm that this is what indeed happening.

Some people may find this exciting because it could presage the coming of dino-chickens. But no one has any idea of how long it would take to figure out how to reverse the rest of a bird’s body. A chicken with nothing more than a snout, by this measure, is profoundly underwhelming.

But for those who are interested in how evolution actually happened, it’s already very thought-provoking. For example, the scientists picked out two proteins to block specifically to turn beaks into snouts. To their surprise, this procedure simultaneously changed other bones in the skulls of the birds, turning them back to dinosaur-like shapes.

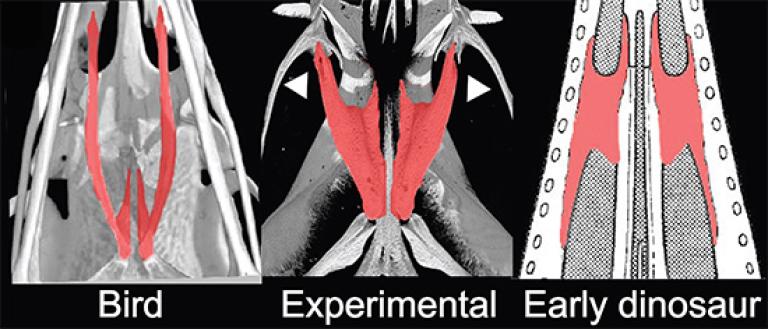

When birds evolved beaks, other parts of their head was also undergoing some evolutionary changes. The palate bones in the roof of their mouth became very thin, serving mainly to transmit forces from muscles at the back of the head to the beak. When the scientists blocked proteins in chicken embryo faces, they changed the palate bones as well as the beak. This figure, which looks up at the palate from underneath, shows what happened:

Scientists have long known that a single gene can have several effects on an animal. This multi-tasking is called pleiotropy. The new experiment hints that the bird beak didn’t evolve simply through a series of little steps, each having a single effect on bird heads. Instead, birds might have taken some bigger evolutionary leaps.

Originally published May 12, 2015. Copyright 2015 Carl Zimmer.