About 4.567 billion years ago, a quivering bead of magma 93 million miles from the Sun cooled down until it grew a skin of rock. Eventually, it would be named Earth. We don’t know a lot about what the planet was like back then, because that primordial crust is almost entirely recycled–eroded away, pushed back down into the molten depths of the planet, or smashed to bits by the huge impacts that blasted Earth for its first few hundred million years.

Geologists have wandered the planet to find scraps of the infant Earth. One mineral that is particularly precious to them is known as a zircon. Tiny zircon crystals can withstand billions of years of abuse–getting ripped out of their original rock, incorporated into new rocks, heated up, and squeezed at tremendous pressures–and yet still retain their original chemistry. Zircons have the added attraction of holding onto radioactive isotopes such as uranium. Over billions of years, the uranium decays at a steady rate into lead. By measuring the atoms of uranium and lead in a zircon, scientists can get a tight estimate of the zircon’s age.

In 2001, scientists digging at a site in the Australian outback called Jack Hills found a zircon dating back about 4.4 billion years. It broke all records for the oldest zircon, and no one has broken its record since.

Estimating the age of zircons from over four billion years ago pushes science’s powers of detection to their limits. And so it’s no surprise that the age of the Jack Hills zircon has been the subject of debate.

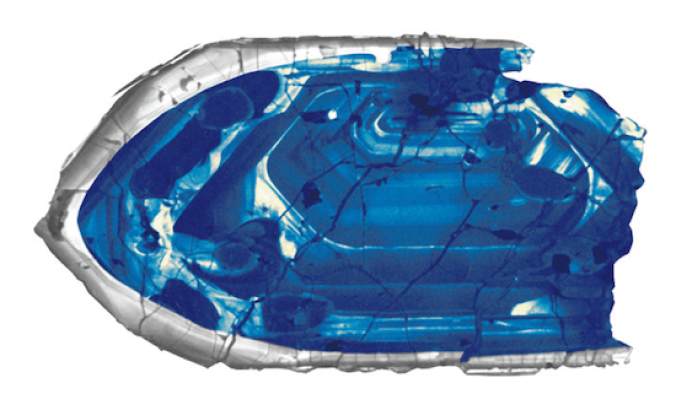

Geologists are constantly raising these challenges and then meeting them. Yesterday in the journal Nature Geoscience, John Valley of the University of Wisconsin and his colleagues published a new study of the Jack Hills zircons. They performed a kind of geological X-ray, mapping the uranium-derived lead atoms from across a zircon grain to figure out how much they’ve moved around.

The lead has indeed moved, Valley and his colleagues have found, but only a little. It has gathered into clumps that are too small and too closely packed to throw off the geological clock. The 4.4 billion-year age stands.

In other words, the Jack Hill zircon existed in rocks that formed about 200 million years after the formation of the planet. That’s a long time for us mere humans, but it’s about four percent of the lifetime of the Earth. Looking inside the Jack Hills zircon, geologists have found hints that they formed in a cool crust below a liquid ocean. If that’s true, then it also means the Earth was hospitable for life by then.

But there’s only so much insight you can get from a zircon that’s twice the thickness of a human hair. What geologists would love to find is an honest-to-goodness rock from 4.4 billion years ago–something you could hold in your hand. The oldest rocks with an uncontested age date back 4 billion years ago–400 million years younger than the Jack Hills zircon. If geologists could find rocks from 4.4 billion years ago, filled with a variety of minerals, they could learn much more about the early Earth.

In the March issue of Scientific American, I have a story about rocks that may indeed be 4.4 billion years old–the oldest rocks on Earth, in other words. But these rocks, along the coast of Hudson Bay, have inspired an intense debate among geologists, some of whom argue that they’re actually much younger. The science is fascinating, and the stakes are big. You’ll need to buy a copy of the issue or access the story through a subscription, but I hope you’ll find it worth the effort.