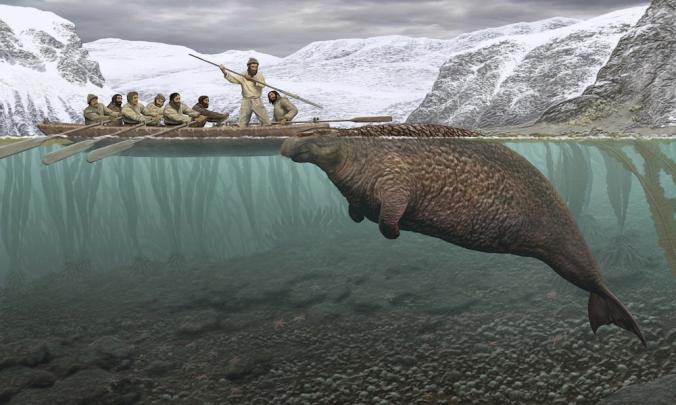

ILLUSTRATION COPYRIGHT CARL BUELL

The Steller’s sea cow is gone. This mega-manatee swam the North Pacific for millions of years, and then in the 1700s humans hunted them to extinction. Today on the front page of the New York Times, I write about a warning from a team of scientists that if we keep on doing what we’re doing now–industrializing the ocean and pouring carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in greater and greater amounts–a lot of other marine animal species will go the way of the Steller’s sea cow.

Yet this story is actually a fairly hopeful one. The scientists compared the pace of extinctions at sea to those on land and found that the oceans are basically where the land was in 1800–with relatively few extinctions yet, on the verge of massive changes to the habitat that could wreak much bigger havoc. The oceans still have a capacity to recover, if we choose to let them.

It’s hard to strike that balance, but it’s important. By coincidence, a group of marine biologists has just published a provocative opinion piece calling for more skepticism about “ocean calamities”–the claim that the oceans are getting hit with some global shock of one sort or another. (You can read the piece in Bioscience for free.) They complain that too often scientists see a small-scale change in one region of the ocean and blow it up to a global catastrophe. The scientists pick apart some of these cases, such as the belief that jellyfish are taking over the planet. The strongest evidence for their rise turned out to be a natural increase of one population of jellyfish that is part of a natural cycle.

That doesn’t mean that thee are no ocean calamities. The scientists see strong evidence for devastation from overfishing, for example. And that doesn’t mean that dangers that don’t seem to have had big impacts yet won’t have them in the future (see ocean acidification). But leaping to the apocalypse based on limited or ambiguous evidence is bad science and bad policy, the scientists argue:

We conclude that a robust audit of ocean calamities, probing into each of them much deeper than the few examples provided here, is imperative to weeding out the equivocal or unsupported calamities, which will confer hope to society that the oceans may not be entirely in a state of near collapse and which will provide confidence that the efforts by managers and policymakers targeting the most pressing issues may still deliver a healthier ocean for the future.

I wanted to check in with the authors of the Bioscience piece about the new study I wrote about for the Times. If they thought this new study was an egregious case of calamity-mongering, I needed to know that, and I would make it clear in my piece.

But that’s not what I found. When I spoke to Robinson Fulweiler, a marine biologist at Boston University, she said, “I was really excited to read their paper, and I actually felt good about their conclusions.” She thought the scientists did a good job of gauging what’s happened to the oceans so far, the risks they face in the future, and–importantly–the steps that we can take, armed with our knowledge of the situation.

When we’re contending with our effects on the planet, it may be tempting to go limp and say we’re all doomed, or to wave it off as some huge delusion. But the reality of the oceans calls for a different response altogether.

Originally published January 16, 2015. Copyright 2015 Carl Zimmer.