Mimicry is one of the eeriest feats of evolution. An insect doesn’t know what a leaf looks like, and yet some species have evolved to resemble leaves down to the finest details. Their mimicry emerges from the ruthless cycle of evolution. The ancestors of leaf insects produced lots of genetic variation, thanks to mutations and mating. Some of that variation affected how they looked. Birds have been feasting on the insects for millions of years, and their victims have tended to be the easiest ones for them to see against their leafy background. The insects that were harder tended to survive and reproduce. Over time, evolution acted like a sculptor, turning an ordinary insect body into a shape that blended in with the surrounding leaves.

But the mimicry of leaf insects, as cool as it may be, is simple stuff compared to what’s evolved in other species.

The leaf insect mimics just one other living thing: a leaf. But there’s another kind of animal that can mimic two different species, and for entirely different effects.

That animal is the cuckoo. Instead of building their own nests, female cuckoos slip into the nests of other birds and lay their own eggs. They’re parasites, although not of the sort we may be familiar with, like a tapeworm that glides into our gut and exploits us from within. Cuckoos exploit the parental care of their hosts.

When a host bird returns after a visit from a cuckoo, it may recognize an alien egg in its brood and knock it out of the nest. But often it won’t. That’s because the cuckoo is very good at mimicking its host species. The shells of their eggs often closely match those of the species they exploit. Unable to tell the difference between the parasitic eggs and their own, the host birds will care for them all.

When the cuckoo chicks are born, they often will throw the other eggs out of the nest. It will even kick out the host’s chicks, to starve to death on the ground. The murderous baby birds then open their mouths like any chick hungry for food. In some cuckoo species, chicks look remarkably like those of their foster parents. They even sing like their hosts. All this mimicry triggers responses in the host birds to feed the cuckoo chicks as if they were their own. Remarkably, the host will keep feeding the cuckoo long after you’d think it should notice something’s wrong. For example:

But it turns out that cuckoos mimic a second kind of animal to succeed in their parasitic ways. They don’t just pretend to be their hosts. They also pretend to be their hosts’ enemies.

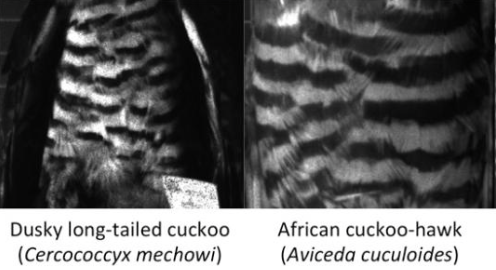

In many species of cuckoos, the adult birds develop stark stripes on the feathers covering their belly. The barred pattern looks remarkably like that of hawks and other raptors.

Why should cuckoos look like hawks–and why is the similarity most striking on their belly? Consider the fact that in order for a baby cuckoo to fool its foster parent, its mother first has to get into the nest to lay her eggs. The host bird doesn’t just sit by and let this happen. Instead, it will often try to chase off the cuckoo intruder.

Cuckoos have evolved tricks to short-circuit this defense. In some species, a male cuckoo will fly around a nest, luring the host bird into a chase. While the nest is unguarded, his female partner slips into the nest and drops her eggs.

Given the evolutionary arms race in which cuckoos and their hosts are locked, one explanation for those hawk-like bars comes knocking loudly at the door. What if the cuckoo has evolved to look like a hawk?

A host bird looks up and sees barred feathers zooming into view. There’s no time to mull a decision–if the host bird doesn’t instantly fly away, it will be killed by the hawk to whom those stripes must belong.

Scientists have tested this idea in several ways. In some experiments, they’ve built cuckoo models and presented them to host birds. The birds are more likely to attack a model without bars than one with them.

But most of this work has been carried out on just one pair of birds–the common cuckoo and the Eurasian sparrowhawk. Even if this one cuckoo species is pretending to be a raptor, it’s hard to know if the many other cuckoos that live across the Old World are pretending, too.

And there are other potential explanations for cuckoos to be striped. Cuckoos will lurk in trees before springing on a victim’s nests, waiting for the right moment to swoop in. Maybe the stripes serve as camouflage.

Two biologists at the University of Cambridge, Thanh-Lan Gluckman and Nicholas Mundy, decided to test the predator mimic hypothesis in a new way. Other animals, they knew, have evolved to look like dangerous models. The English naturalist Henry Bates was the first scientist to discover this phenomenon as he studied butterflies in the Amazon in the late 1800s. Some of the butterflies were poisonous, and their bright markings warned off birds. Bates noticed that other butterflies that were harmless had similar markings. These so-called Batesian mimics could ward off birds without putting in the extra energy to store toxins in their tissues.

What’s most striking about the butterflies Bates discovered is the fine detail of the mimicry. The poisonous butterfly species in one part of the Amazon look different from the species in other parts. Each mimic species has evolved to look identical with the poisonous species that overlaps its range. That’s probably because birds recognize the markings of the poisonous butterflies that they encounter–either through instinctive reactions, or by learning from bitter experience. There’s no advantage in looking like a poisonous butterfly from Peru if you’re a harmless butterfly in Venezuela.

If cuckoos are indeed mimicking raptors, then they are also Batesian mimics. They are pretending to be an enemy of their hosts–in this case, a predator rather than poisonous prey. So Gluckman and Mundy wondered if, like Batesian butterflies, the cuckoos match their local raptors, too.

To find out, the scientists plunged into the collection of bird specimens kept by the Natural History Museum and took photographs of the barred bellies of a number of cuckoo species. The scientists also took photos of the raptors that live alongside them. Rather than eyeball the patterns, the scientists ran the pictures through a computer program. Taking into account how bird vision works, the scientists transformed the images to what the birds would see. They then transformed the feather patterns from each species into mathematical representations. It was then possible for the scientists to calculate how similar the patterns were to each other.

All the cuckoos, Gluckman and Mundy found, strongly resembled a species of raptor that shared their range. None resembled a species outside its range. While this tight link was striking, Gluckman and Mundy investigated some alternative explanations for its existence.

Perhaps it was due not to cuckoos mimicking local raptors, for example, but cuckoos and raptors both adapting to the same ecology. Maybe living in dim jungles or bright savannas influences how any bird’s stripes evolve. But when Gluckman and Mundy looked at cuckoos that lived in similar ecosystems, they didn’t find similar stripes.

Instead, it looks as if cuckoos are indeed Batesian mimics. They are evolving to look like local raptors to scare off their hosts, so that they can lay eggs in their nests.

This new study is just one of a growing number revealing just how deep the sophistication of mimicry can go. Mimics don’t just mimic one feature in another species. They can be multi-dimensional in their disguises. An ant known as Protomognathus uses mimicry to turn other species of ants into its slaves. The queen invades a colony and releases chemicals that prompt the workers to treat her as one of their own. The queen’s offpspring have the look and smell of their host’s, tricking the workers into feeding them.

As I marveled about the double-con of cuckoos, I couldn’t think of another animal that pulls a two-species scam. I asked Gluckman if she knew of any. She didn’t, but asked around her lab.

Someone drew our attention to the Spicebush Swallowtail butterfly. As a catepillar, it avoids getting eaten by birds by taking on the appearance of bird droppings. When it gets bigger, it takes on the appearance of a snake. And when it develops into an adult, it mimics a poisonous butterfly.

Which just goes to show, when you wonder whether something exists in the natural world, usually the answer is yes.