Charles Darwin was a DIY biologist. He was not a professor at a university; he was not a researcher at a government lab. As a young gentleman, he had the right connections to tag along on the voyage of HMS Beagle as an unofficial, unpaid naturalist. Once he came home, he spent most of his time at his country estate, where he ran decades of experiments on orchids and rabbits. He played a bassoon to earthworms to see if they sense low noises. He made painstaking observations on other species. He spent years peering through his personal microscope at barnacles. He spent afternoon following ants around his lawn. To add to his personal discoveries, he wrote to a global network of friends and acquaintances for every scrap of information he could find that seemed relevant to his theory. While Darwin took advantage of every tool a Victorian naturalist of means could get his hands on, they were quite simple compared to the equipment evolutionary biologists use today. No DNA sequencers or satellite databases for him.

The simplicity of his tool kit and the grandeur of his work makes Darwin exceptional enough in the history of science. What makes him even more so is our ability, some 150 years later, to get to know his DIY biology in deep detail. Darwin described many of his projects in his books, and the University of Cambridge still has hordes of his letters on file. In recent years, this Himalaya of information has become available in searchable form online at places like The Darwin Correspondence Project and Darwin Online.

Ned Friedman, a botanist at Harvard, has come up with an intriguing way to use Darwin’s life to teach the basics of evolution. He and a team of graduate students have created a freshman seminar called “Getting to Know Darwin,” in which the students recreate ten of Darwin’s experiments and observations, spanning his life from his college days to the work on earthworms, which he carried on during his final years. To get an intimate feel for Darwin’s ideas and work, the students read his letters in which he discusses each topic. They then run experiments very similar–or in same cases, identical–to the ones Darwin ran himself.

Friedman has now gone the extra mile and put all the details of the class online at the Darwin Correspondence Project site. You can read about each lesson, such as the one on biogeography–the science of why species are where they are. Friedman’s students do experiments with seeds in fresh water and salt water to see how plants could get to remote islands. Some ducks’ feet obtained from a butcher shop allow students to see how Darwin figured out that birds could transport plants to new homes.

From my inspection of the site, I think it would be great not only for college courses, but for high school and even for curious families. Maybe it’s time for me to dump some seeds in some salt water…

Friedman explains the project in this video:

Darwin Resources from Darwin Correspondence Project on Vimeo.

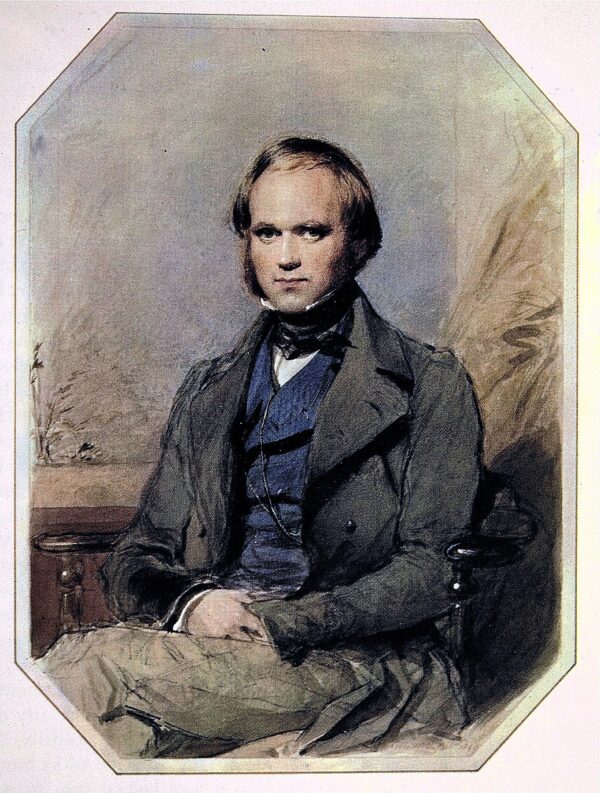

[Portrait of Darwin: Wikipedia]

Originally published January 28, 2013. Copyright 2013 Carl Zimmer.