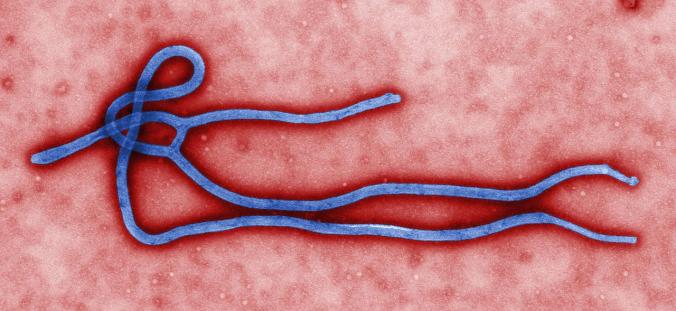

I have a story in the news section of today’s New York Times on the past and future of Ebola. There is so much anxiety and curiosity about the virus that it seemed like an opportune time to check in with a bunch of evolutionary biologists who study Ebola–as well as other viruses. In my piece, I make two basic points: 1) the scientists I’ve spoken to don’t think that the virus currently spreading around West Africa (and beyond) is some freakish mutant, and 2) it’s very unlikely that during this outbreak it will transform into some fundamentally different–and more dangerous–pathogen.

Reporting a story like this is a bit like dipping a bucket into a burbling fountain. There’s just too much to capture in a single article–especially a standard 1000-word newspaper piece. Fortunately, the Internet provides us with infinite overflow space.

So here I’d like to just expand on a couple of the more compressed points in my story. And I’ll extend an invitation to you, dear reader, to use the comment section below to post any questions my story raises in your mind. I’ll do my journalistic best to answer them in updates to this post. (I’ll also note any revisions I have to make to the post to correct any errors I’ve made.)

1. Ebola is 20 million years old? How do you know? Viruses are terrible at leaving fossils, but they can leave their imprint on their hosts.

Every now and then, a virus will insert some of its DNA into its host’s genome, and that viral DNA gets passed down their descendants for millions of years.

Our own DNA is riddled with viral DNA, which makes up at least 8 percent of the human genome. Most of it has mutated into useless baggage, but some has been transformed into useful genes (useful to us, that is). I’ve written hereabout how virus proteins are essential for our placentas to develop.

The presence of the same virus at the same spot in two different host species can give a clue to its age. That’s because the virus must have infected the common ancestor of the two species.

In recent years, scientists have been finding DNA from the lineage of viruses that includes Ebola (called filoviruses) in mammal genomes. Last month, they published an especially interesting study on this fossil virus material. They found the same viral DNA at the same spot in two species of rodents–hamsters and voles. And this DNA is more similar to Ebolavirus than to its closet relative, Marburg virus. Hamsters and voles share a common ancestor that lives roughly 20 million years ago, and so that means that Ebola viruses had split off from Marburg virus relatives at least that long ago.

There’s even some evidence that some of this Ebolavirus DNA is performing some useful jobs in its mammal hosts. It would be fascinating to learn more how this deadly virus has been domesticated.

2. Hasn’t Ebola gone airborne already? There’s been some suggestive evidence in the past, but scientists have questioned whether transmissions that seemed like they were airborne were just the result of short-range droplets–not long-range aerosols. Here is a report from July in which Canadian researchers tested out a bunch of nasty viruses for how easily they could be transmitted by air between monkeys. “In the current study,” they write, “two NHPs [non-human primates] were lethally infected with EBOV [Ebola virus], and no EBOV virus or antibodies to EBOV GP [a virus surface protein] were detected in the neighbouring uninfected NHPs for up to 28 days after the challenge date.” Here is a lengthy blog post from Heather Lander on this study and previous ones. And here is virologist Vincent Racaniello with more thoughts on the issue.

3. Mike Lewinski asks:

What is the likelihood that ebola might adapt to transmission by tick or mosquito? I know that it evolved to infect mammals and there’s no evidence it can infect insects now. Is infection of the insect cells a necessary prerequisite to transmission by insect?

As you’ve noted elsewhere, ticks are veritable “swiss army knife of disease vectors” and carry several different viruses such as Powassan virus which killed a woman here in Maine a year ago. Are any of those closely related to ebola?

My hunch is that this is another wolves with wings scenario.

One team of scientists have reported that they could get Ebola to replicate in mosquitoes, but another team failed to when they replicated the experiment. “This virus does not replicate in arthropods [mosquitoes and ticks] tested to date,” they concluded. In a new review on Ebola and related viruses, another pair of scientists stated, “The role of vectors [such as mosquitoes] is unlikely, but not known.”