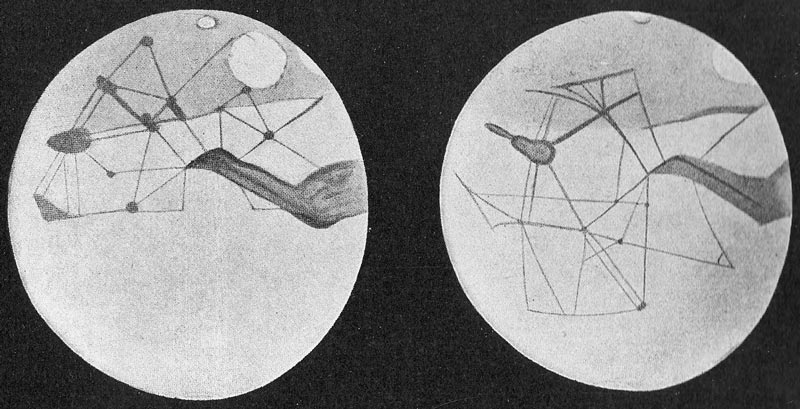

In the late 1800s, prominent astronomers declared that Mars was criss-crossed by canals–evidence, they declared, of an advanced civilization. But in the early 1900s, astronomers gazed through more powerful telescopes and discovered that the canals were mirages.

The astronomer Percival Lowell, who had become the leading champion of the canals, scoffed at the new findings. Hedeclared that the criticism came “solely from those who without experience find it hard to believe or from lack of suitable conditions find it impossible to see.”

Although the new evidence led many astronomers to abandon Lowell’s position, he never retracted his claim. It wasn’t until five decades after his death in 1916 that space probes finally went into orbit around Mars and sent back close-up pictures of a canal-free Red Planet.

I’ve always been fascinated by the way science casts aside bad ideas. For most of us, it’s easy to assume that science shakes them off quickly, but the truth is that it can take quite a while for the process to play out. Recently I was invited to contribute a piece to the new “Sunday Review” section of the New York Times, which just debuted this week. I wrote an essay on this phenomenon, which has been dubbed “de-discovery.” I drew on three recent examples of high-profile research that many other scientists have declared to be wrong–arsenic life, clairvoyance, and a link from chronic fatigue syndrome to a virus called XMRV.

To keep my essay from exploding into a novella, I had to limit myself to just these three examples–but I could have picked many others. You just need to check out a blog like Retraction Watch to see how important this part of the scientific process is today. The first draft of my essay actually started out with a fourth example, which I decided to cut it in the end. It’s a peculiar case of a de-discovery of a de-discovery.

In 1981, the late Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould published an influential book about racism and science, called The Mismeasure of Man. Gould argued that social influences could lead scientists to misinterpret their data to suit their beliefs about European superiority. One of his key examples was the work of a nineteenth century anthropologist named Samuel George Morton.

Morton collected 1,000 human skulls from around the world and measured the size of their brain cavities with seeds or lead shot. Gould re-analyzed Morton’s data and published his results in 1978 in the journal Science. He declared that Morton fudged his measurements to ensure that Caucasians would end up with the biggest brains.

In 2000, a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania named Jason Lewis started to measure Morton’s skulls for a research project of his own. He was interested in the ways different human populations adapt to different climates—including changes in the shapes of their skulls. It was then that Lewis learned from his advisors about the controversies swirling around the skulls. (He was born a year after The Mismeasure of Man was published.)

As Lewis carried out his own measurements, he gradually realized that Gould had been wrong. He then set out to systematically investigate the matter—taking three years to measure Morton’s skulls, and then another five years to work through Gould’s claims.

Lewis, who just finished earning his Ph.D at Stanford University, wrote up the results with his colleagues and submitted a paper in 2008 to the journal Current Anthropology, which had published a less detailed critique of Gould’s paper in the 1980s. The journal rejected Lewis’s paper, eventually informing him that it was not important enough.

The researchers had better luck with PLOS Biology, which published their paper earlier this month. Lewis and his colleagues presented evidence that Morton did not bias his findings at all. Instead, the researchers conclude, it was Gould who used shoddy statistics. There are many sound scientific reasons to reject racist views of human biology, they argue, but an unfair trashing of Morton’s research isn’t one of them.

“Our analysis of Gould’s claims reveals that most of Gould’s criticisms are poorly supported or falsified,” they write.

When I was researching my essay, I asked Lewis about what he thought of science’s self-correcting process now that he’s finally done with his exploration of Gould and Morton. He has decidedly mixed feelings.

“We can come back thirty years later and get the story straight,” he told me. “But it takes thirty years.”

As I write in my essay in the Times, there are certainly ways to make dediscovery a smoother, faster process. But in an age of instant viral communication, I think we’re going to remain frustrated by inescapable lags.

[Image: Wikipedia. Thanks to folks on Twitter for pointing me to Martian canals as a textbook case of slow dediscovery]

Originally published June 27, 2011. Copyright 2011 Carl Zimmer.