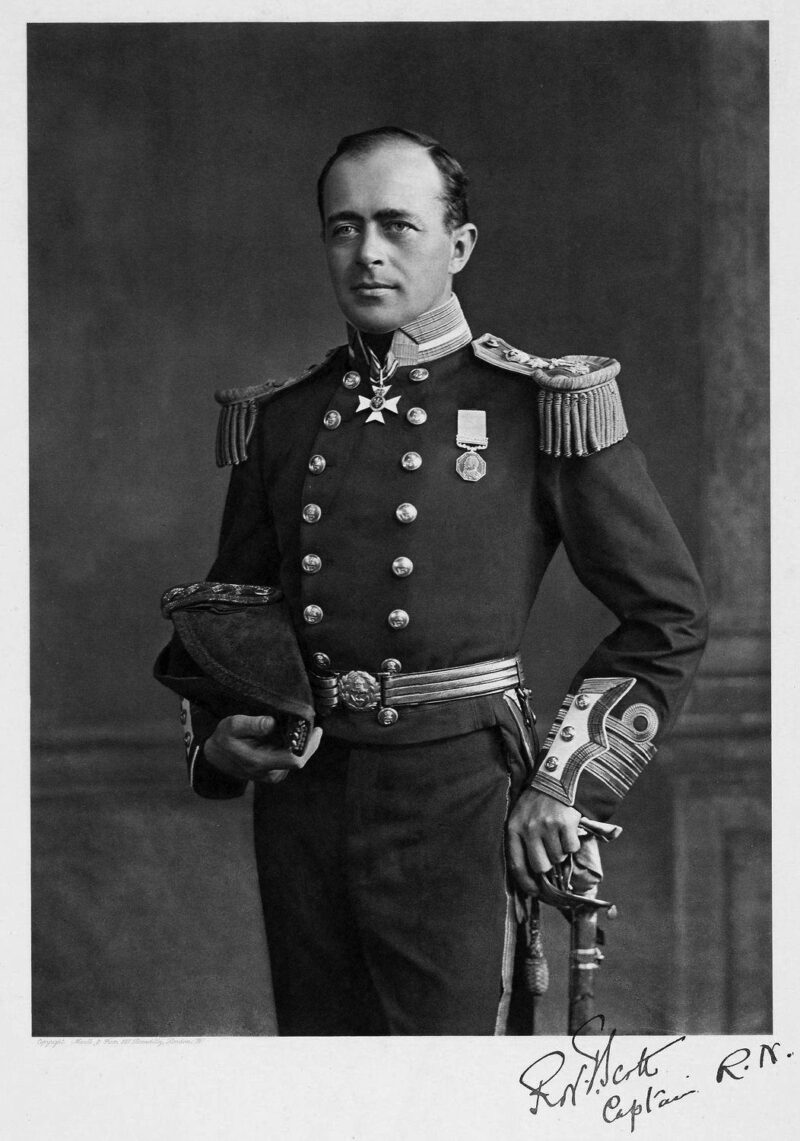

On March 29, 1912, Robert Scott and two fellow explorers huddled in a tent during a fierce Antarctic blizzard. They had landed on the edge of Antarctica five months earlier, hoping to be the first people in history to reach the South Pole. They succeeded in reaching the Pole, but it was a bitter success. They discovered that another team, led by Roald Amundsen, had gotten there first. So Scott and his team turned back and began the 800-mile journey back to the sea. They hauled sledges themselves, without the help of dogs. The plunging temperatures increased the friction of the snow, so that they had to put in as much effort as they would to haul the sledges through sand. On February 4, Edgar Evans dropped dead. On March 16, Laurence Oates, barely able to walk, simply left the camp and never came back. A blizzard on March 20 left them unable to leave their tent.

“I do not think we can hope for any better things now,” Scott wrote in his diary nine days later. “We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far.” And indeed he likely died that day. Scott and his crew were finally discovered eight months later.

Scott may not have been the first person to reach the South Pole, but he did earn a different kind of distinction: “the greatest human performances of sustained physical endurance of all time,” in the words of University of Cape Town sports scientist Timothy Noakes. All told, Scott probably burned about million calories. Each day he and his fellow explorers burned around 7,000 calories, about four times the rate of a man at rest.

Scott’s accomplishment was exceptional not just for a human, but for any animal. Animals rarely push their metabolism beyond about four times their resting rate for any length of time. A cheetah may explode into a sixty-mile-an-hour sprint, but for only a few seconds. Most animals that push themselves hard–birds racing around to find food for their chicks for days on end, for example–only push themselves about four times above their resting metabolic rate.

In 2007, however, a small bird left Scott in the dust. Scientists discovered that bar-tailed godwits could fly from Alaska to New Zealand, non-stop. Their metabolism, scientists found, rose to about eight times their resting rate. And it stayed there, 24 hours a day, for nine days. And while Scott could refuel on his journey by eating horse meat and pemmican, the bar-tailed godwits fasted for their entire 7,000 miles journey.

As I report in the lead story of the Science Times in tomorrow’s New York Times, research now shows that the bar-tailed godwit has some company. Using sophisticated new location-tracking devices, scientists have discovered other species several travel several thousand miles without a break.

I also write about the deeper significance of these new results. How do these birds achieve these awesome treks. And why? In a new paper, the Swedish biologist Anders Hederstrom argues that birds like bar-tailed godwits aren’t all that unusual. Lots of birds that go on much shorter migrations have many of the same adaptations as the champions–the ability to store up fat, an ability to navigate long distances, an efficient body shape, and so on.

Theunis Piersma, a Dutch biologist, offered up a provocative idea for the evolution of ultramarathoning birds. Their migrations may be able to shift quickly from short to long. Birds have a huge potential to work hard, without the need for long-term physical evolutionary changes coming first. All they need is a change in behavior, and their bodies will meet the challenge. Once they shift their behavior, natural selection may well favor physical changes that help them go long distances. (Piersma will write about this at length in his upcoming book, The Flexible Phenotype.)

For Piersma, what’s really interesting is why godwits and some other birds push so hard, while most other animals don’t. Piersma thinks that laziness is, for the most part, adaptive. If animals push themselves beyond about four times their resting metabolic rate, they usually have to pay dearly. They become vulnerable to predators and disease, for example. When scientists have added extra chicks to the nests of kestrel hawks, for example, the parents have to work harder to feed them. As a result, the scientists found, the parents became more likely to die. When scientists add little weights to bees that are buzzing around gathering nectar, the bees are also more likely to die. And Scott himself is a grisly illustration of Piersma’s tradeoff. His foot became infected so badly, he wrote, that “amputation is the best I can hope for.”

Flying over open seas, however, may allow some birds to escape this trade-off. Predators and parasites can’t catch them when they’re hundreds of miles from the nearest land. When bar-tailed godwits land after flying 7,000 miles, they can just take a long nap without worrying about being eaten. The very things that might make exhaustion more dangerous are missing from their migration.

For more, check out my story.

Update: And be sure to check outthe great interactive maps.

[Images: Scott, Wikipedia/Godwits, Robert E. Gill]

Originally published May 24, 2010. Copyright 2010 Carl Zimmer.